Image courtesy of Nuestro Stories.

The name "Rosa Flores" probably doesn't sound familiar to you. Like so many thousands of women, Rosa Flores worked tirelessly in a garment factory for paltry wages and in terrible conditions. Until one day, she said, "enough is enough," and joined a strike.

Flores and hundreds of other women decided to raise their voices and change history forever.

A Forgotten Strike

After World War II, low-wage, labor-intensive industries moved to the Southwest, where most of the workforce was made of Chicanas.

These women represented 85 percent of the employees of the Farah Company, a men's trouser factory.

Farah was one of the largest companies in Texas, with five plants in El Paso alone and many others in San Antonio, Victoria, and New Mexico.

The company's founder, Willie Farah, was a Lebanese-American and the man behind the Farah Manufacturing Company. In El Paso, Farah was seen as a local hero who offered parties, gifts, and free medical care to his employees.

Behind closed doors, the reality was different.

Farah Manufacturing Company employees were subject to mistreatment — from harassment by supervisors to non-existent health and safety standards.

As Kim Kelly recounts in her new book "FIGHT LIKE HELL: The Untold History of American Labor," sewing machine needles sometimes jumped out and punctured the fingers or eyes of Farah employees. There was no maternity insurance, and workers lost their seniority once they had to leave work to have a baby.

And then the women organized

Farah Company's employees first organized in 1969. They began a union drive to join the Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America (ACWA). However, the company started harassing and firing union supporters.

Despite the scare tactics, support for the union grew among the company's workers, culminating in a strike in May 1972.

It appeared then that the Southwest was beginning to cease to be a haven for non-union shops.

In September 1970, Silvia M. Treviño left her job and was the first to walk out of the factory and initiate a protest. A sea of women followed in her wake, among them Rosa Flores, who would become the face of the strike.

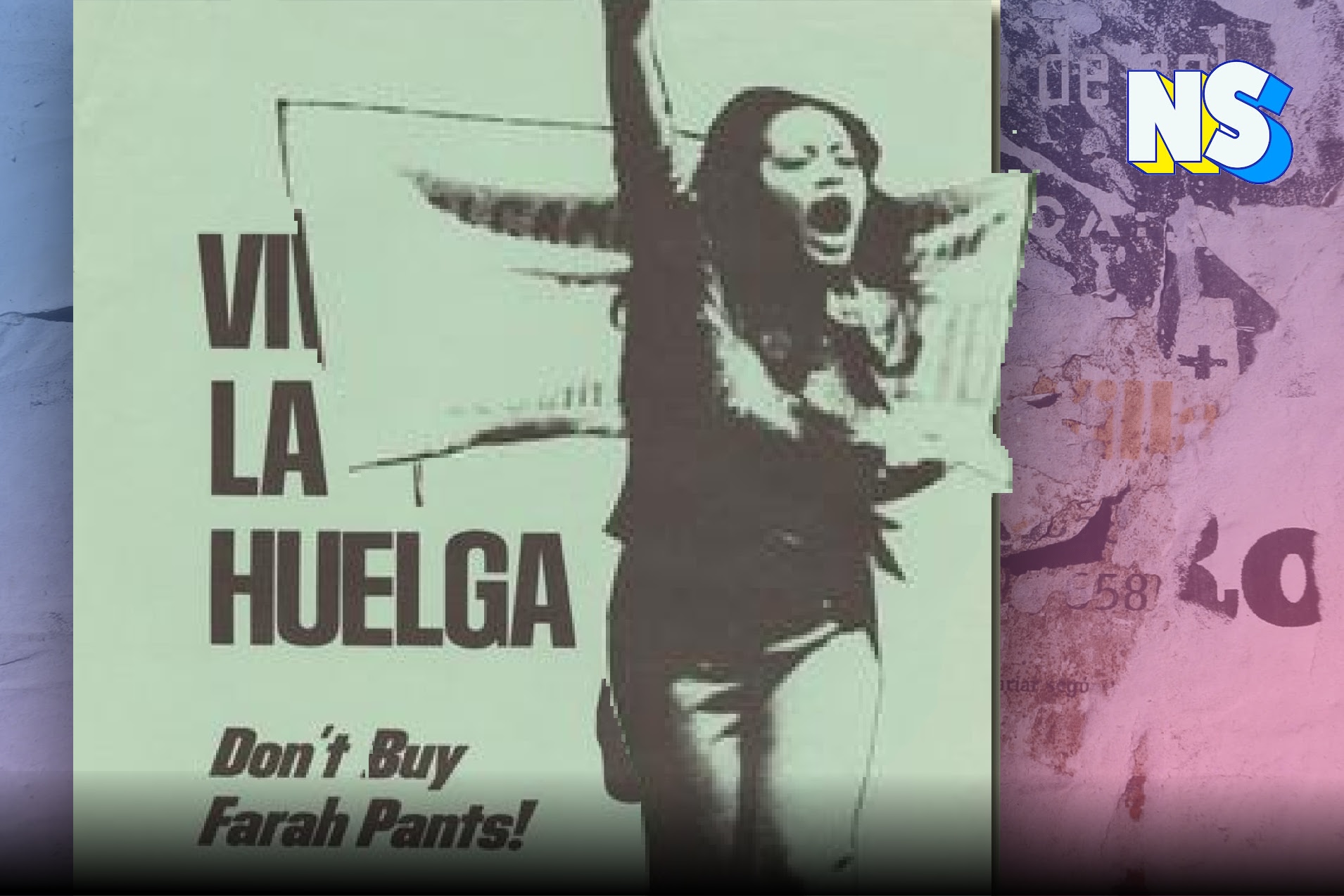

Flores appeared in front of the cameras raising her fist and shouting, "¡Viva la huelga!" (“Long live the strike!), and has since become the image of the protest and an inspiration to millions of Latino workers nationwide.

The people's love for Willie Farah discredited the strike, portrayed by the media as intransigent and dishonest. Protesters were verbally and physically assaulted, and tensions within the Chicano community itself began to escalate.

As in any power play, the fired strikers were replaced, suffered economic hardship, and worked wherever they could. The $30 they received in union benefits was not enough.

If the strikers got another job, they had to keep their activities secret because if it became known that they were Farah strikers, they would be fired.

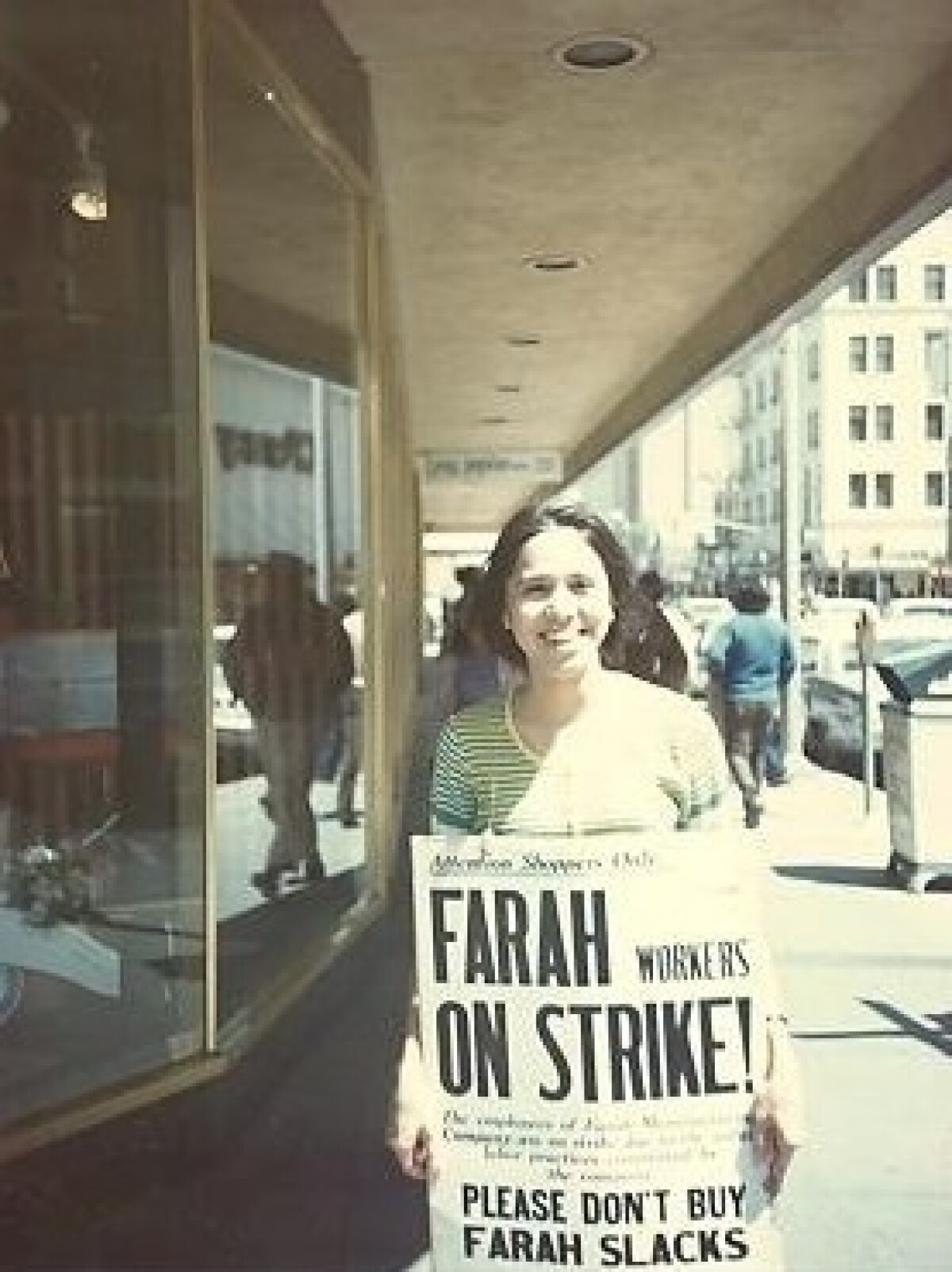

Despite these difficulties, the women received support from the ACWA, which sent organizers to El Paso, helped organize the boycott of Farah's pants, taught classes, and showed films.

The Catholic Church was another institution that supported the movement, offering its headquarters as a meeting place.

The strike ended in January 1974, and a month later, Farah recognized the union and its demands. Labor contracts thereafter included job security, a company-funded health plan, recognition of the ACWA union, and reinstatement of laid-off employees.

Since then, the strike by the Chicana workers at the Farah Company has become known as "the strike of the century" and set the stage for radical change in the working conditions of millions of workers across the country.