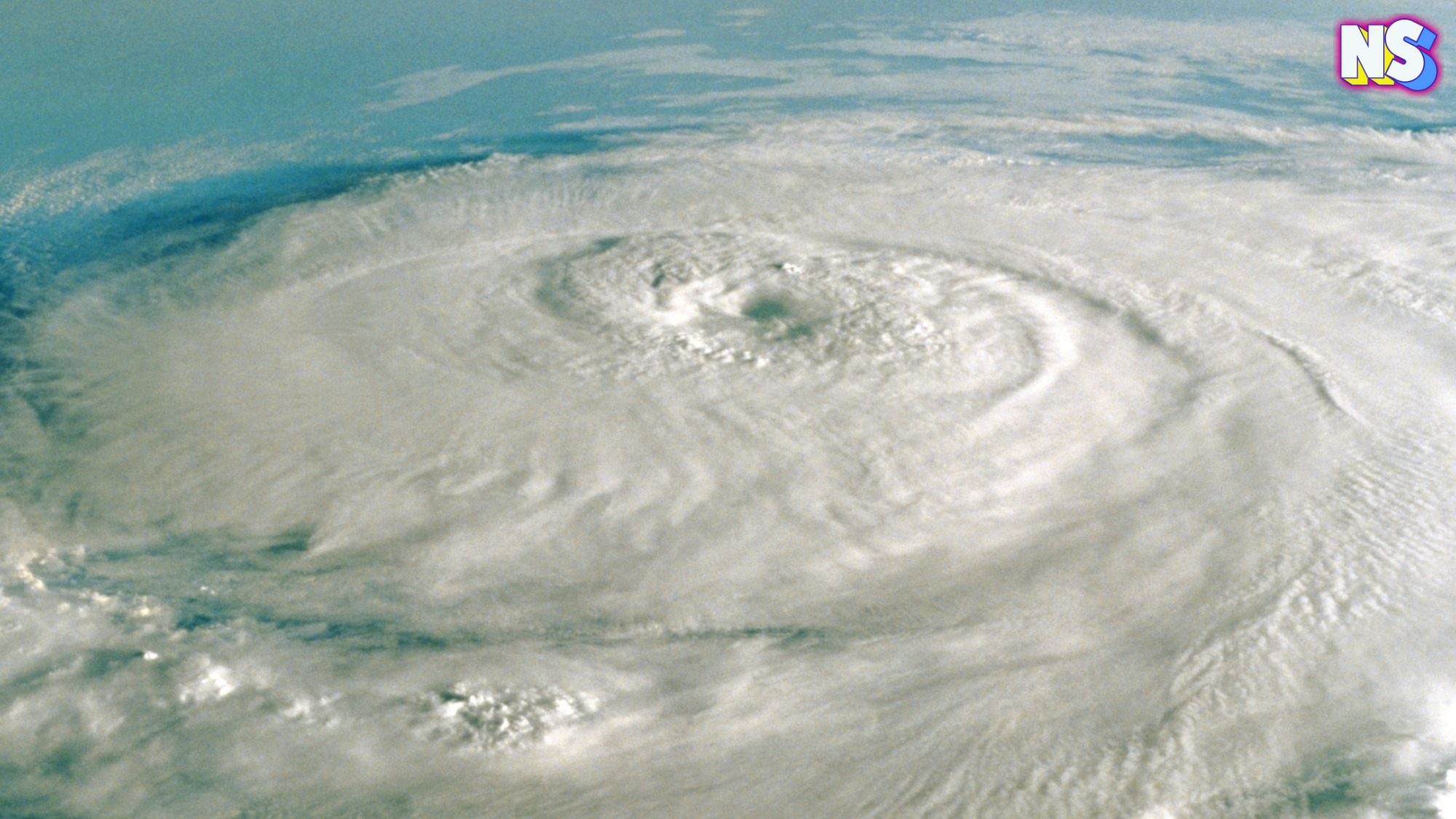

As news of Hurricane Milton makes the rounds on the internet and social media, one story stands out. Anthropologist James L. Fitzsimmons‘ piece “Centuries ago, the Maya storm god Huracán taught that when we damage nature, we damage ourselves” connects modern weather patterns to ancient origins. As one Reddit user commented “A science blog, publishing an article about climate change, written by an anthropologist, that cites an ancient Mayan god ... ” Turns out, Hurricane Milton’s destruction has a strong connection to both the Mayan and Taino cultures. Ancient people knew a "hurricane" was more than a storm. It was a god.

Hurricane Milton’s Connection to the Mayan and Taino people

“The term ‘hurricane’ finds its roots in the Caribbean, where the indigenous Taíno people of the Greater Antilles worshiped a storm deity named Juracán,” the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s official website explains. “This god’s name may also have come from the Mayan god of wind, Huracan.”

The term’s popularity spread across Latin America when the Spanish explorers adopted the words "huracán" and “furacán” to describe the intense storms they had never witnessed before in Europe. “The word eventually became widespread in the English language as European colonial powers expanded their territories and often encountered these powerful storms in the Atlantic basin,” the NOAA adds.

Huracán: The Storm God of the Maya

In the mythology of the K’iche’ Maya, who lived in what is now Guatemala, Huracán was one of the gods responsible for creating the world. He appears in the Popol Vuh, a sacred Mayan text from the 16th century that describes the origins of the universe. According to the myth, Huracán played a key role in shaping the world, but he also embodied the destructive forces of nature. Huracán’s name became synonymous with storms and destruction.

The Taíno: Jurakan, the God of Storms

In the Caribbean, the Taíno people had their own version of this destructive storm god. According to their mythology, the goddess Atabei created the earth and the sky, and from her were born two sons, Yucaju and Guacar. Yucaju was responsible for creating the sun, moon, plants, and animals, while Guacar, filled with jealousy over his brother’s creations, began to tear apart the earth with violent winds. He took the name Jurakan, becoming the god of destruction, wind, and storms.

The Taíno people feared Jurakan’s wrath. He was the source of the powerful hurricanes that would batter their islands, leaving death and destruction in their wake. In their culture, the storm was not just a natural phenomenon but an act of divine fury. They performed rituals to appease the storm god, hoping to ward off the next disaster.

The Spanish Encounter the Storms—and the Word

When Spanish explorers first arrived in the Caribbean in the late 15th and early 16th centuries, they encountered the full force of these tropical storms, as well as the stories told by the indigenous peoples. The Spaniards adopted the Taíno word huracán to describe the violent storms that frequently swept through the islands. For them, it was a fitting name for the terrifying weather patterns they were unfamiliar with but had to endure during their voyages.

The word quickly spread through the Spanish-speaking world, used to describe these intense tropical cyclones. Spanish explorers and settlers passed the term to other European languages, and by the late 16th century, it had entered the English language as hurricane.

Today, the term “hurricane” remains a powerful reminder of the destructive forces of nature, rooted in the mythology of the Taíno and Mayan civilizations. What was once a symbol of divine fury is forever a part of modern meteorology. The core idea, of course, remains the same: hurricanes are a force beyond human control, to be feared and respected.