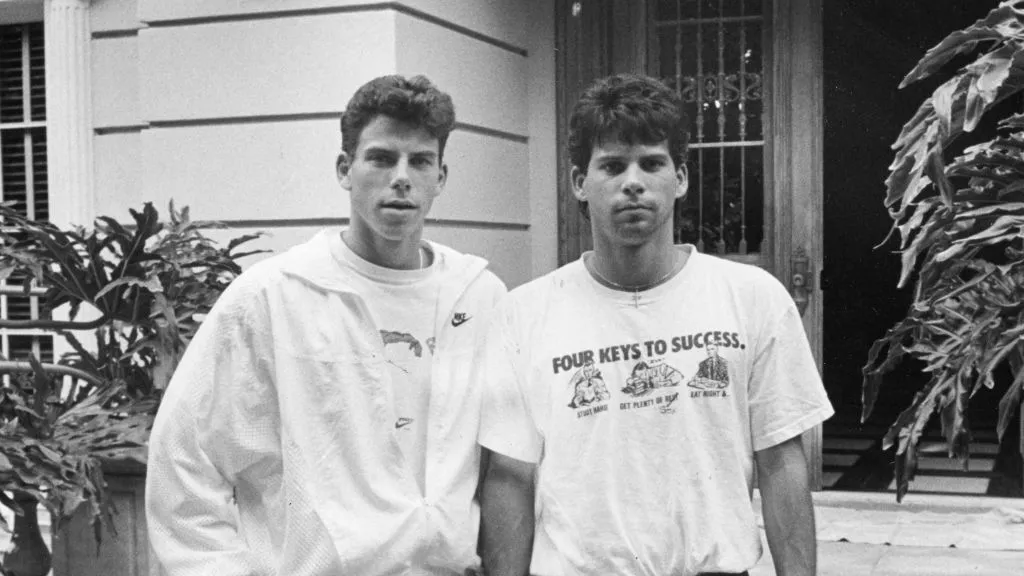

Credit: Rodriguez; Illustration by Nuestro Stories

Where were you when you first heard a Rodriguez song? Were you deep in the annals of some dingy, dusty record store, digging through vinyl, when some pretentious audiophile insisted you listen to that silky sound oozing from his earwax-crusted AirPod?

Maybe you were tuned to your local college FM station with piss poor reception because your school invested in a fledgling football program over proper bandwidth when you desperately asked your phone to Shazam what song was being played aloud.

How would you ever survive not identifying this earworm that sounds angsty, folksy, timeless, and in a lane all its own?

Better yet, my dear, beloved reader, maybe you’re sitting there, righteously indignant, muttering to yourself, half aloud, “What the F%#K is he talking about?”

Who "Rodriguez" Was

Rodriguez was born, seemingly ahead of his time, somewhere between a Cesar Chavez with a guitar and a less-drug-fueled, more-introspective Iggy Pop lyricist. It’s like if Merle Haggard and Bob Dylan had a knife fight.

So to describe this mythical being, I had to focus and go to the source—the one who introduced me to his music: my dad.

"Papá, tell me, what did Rodriguez make you feel back in the early 70s that made you feel the need to share him with me?" I asked my father. His reply? Simple: "Cathartic. Melancholic. This Midwestern Latino got it."

Here’s a bit from the biography I found today on the (mostly) infallible Wikipedia: He was born in 1942 in Detroit, Michigan. The sixth child of Mexican immigrant working-class parents, "Rodriguez quit his music career" in 1976.

"He worked in demolition and production line work, always earning a low income," his bio reads. He remained passionate about social issues and was "politically active and motivated to improve the lives of the city's working-class inhabitants," running unsuccessfully a few times for public office in Michigan.

On stage, the man born Sixto Diaz Rodriguez, simply known as "Rodriguez," was more of a Detroit labor union rabble rouser and had more heart than his common label: Hollywood’s Hispanic Bob Dylan.

He was the antithesis of what people associate with musicianship today.

He did not possess some unfathomable TikTok following in the tens of millions that could be leveraged into brand deals.

He did not enjoy tailor-made tour schedules built organically around where he was getting the most plays on Spotify and Apple Music, as countless indie artists do today with ease.

The ephemeral vanity of being en vogue eluded Rodriguez and left him and his music largely unshaped by the music industrial complex.

How We Tend to Remember

"The Detroit-based Rodriguez did not know how popular he had become in South Africa, where his songs became anthems for the anti-apartheid struggle in the 1970s. Back in the United States, success had eluded him," Reuters explained in a recent article.

And yet, even in his passing this week at the age of 81, countless obituaries and ivory tower pundits ruminate over the fact that his lasting value is somehow tied to his being rediscovered.

You will read about his unsold LPs being rediscovered in Australia and then South Africa. How this serendipitously led to a string of performances in the 1980s Then more obscurity. Then a heart-wrenching, heartwarming 2012 documentary, "Searching for Sugar Man," which follows two South African music fans on their quest to find the elusive Rodriguez,

The success of the documentary led to Rodriguez’s rediscovery by a society that had thrown him away, allowing him to play at some of the world’s biggest and best music festivals in the last decade of his life.

Surely, playing to thousands of fans previously unknown in faraway lands must have been intoxicating.

And, without a doubt, I do hope Rodriguez felt some sick, twisted little vindication for finally making a dollar off of an industry that largely shunned him and voices like his in favor of more Casey Kasem’s American Top 40 hitmakers.

Celebrate by Listening and Not Much Else.

Forget all that jazz for a moment.

Instead, I invite you to deviate slightly from the boilerplate reaction we have every time we lose a great poet we barely took the time to understand while they were here on Earth.

Don’t just investigate the minutiae of their pre- and post-fame existences. It’s really not that difficult. All you have to do is listen to his songs to know the poet, to hear the pain, and to feel one with someone singing your feelings to you. Lose yourself in Rodriguez.

"Because I lost my job two weeks

before Christmas

And I Talked to Jesus in the sewer.

And the Pope said it was none of his God-damned business.

I See my people trying to drown in the sun.

In weekends of whiskey sours"

The desperation of losing your paycheck-to-paycheck right before the holidays Talking to the son of God where trash usually ends up, only to be belittled by the Papacy himself. To then only be left with the sad, sobering effects of "my people" imbibing in debauchery, escapism, and no way out.

If the duty of every folk singer is to hold a mirror to our imperfections while simultaneously celebrating the passing moments of life often discarded by most, then Rodriguez served his country, his people, and his listeners the world over militantly, diligently, and lovingly.

Absorb the raw, real Rodriquez quality. The production value—not of an over-budgeted Beatles sequel in Wings or the endless iterations of Crosby, Stills, Nash, and Young, but of a poor first-generation Mexican American hell-bent on using the one tool no socio-economic Darwinism or market forces could ever strip from him: his voice.

Okay, so you get it. I would just like to celebrate and give thanks to the Man himself, wherever he may find himself now.

Recognizing that Rodriguez never fully reaped the benefits of fame and fortune that come with being a modern-day crooner

One may say that his initial success was fleeting. But his art will stand the test of time.

Alex Valdés is a self-proclaimed devotee to the written word. He lives between Miami, Florida and the open road. And enjoys "thrifting for rugged camera gear and expired film to make abstract photos of nothingness."