Credit: Nuestro Stories

It was in 1917 that the Goodyear Tire and Rubber company began to farm nearly 16,000 acres of land in Litchfield, Arizona. Originally a sprawl of dry, arid desert, Goodyear bought the land with the intention of raising a specific kind of cotton that could be used to create a tire that rode more smoothly. Therefore, making it more valuable to the burgeoning car market.

Goodyear was ahead of their time

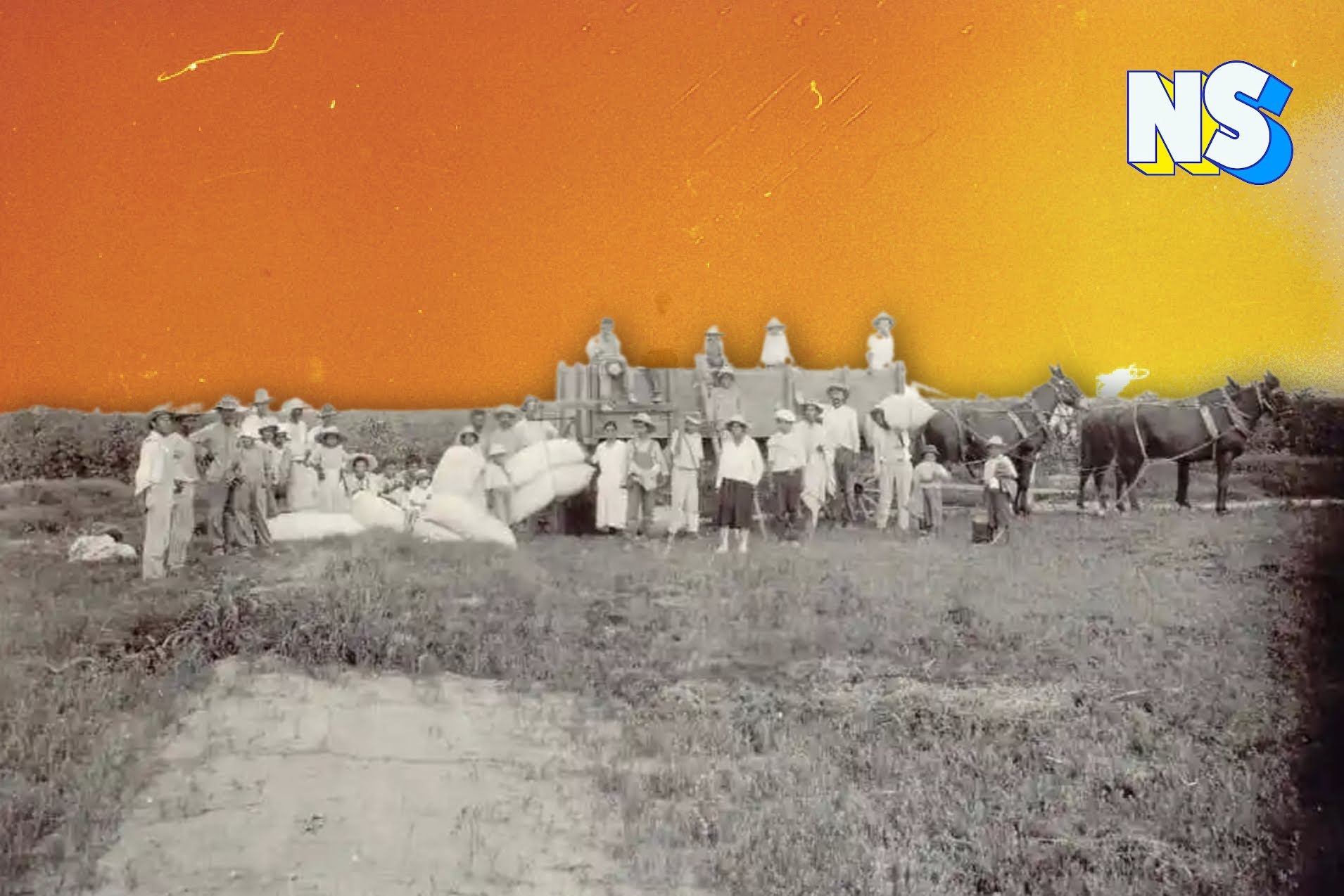

After purchasing the land, Goodyear then brought over 200,000 workers from Mexico to begin clearing the desert. Though the program functioned similarly to the Bracero program – where Mexican workers could cross the border in order to “assist” in the continued growth and economic progress of America – what Goodyear was doing with Litchfield preceded the Bracero Program by over 20 years. Goodyear was aware that there would be no better time to begin.

At the time, there was a heavy stream of workers funneled into America. Between the Mexican Revolution and World War I, hundreds upon thousands were looking for ways to provide for their families as they attempted to rebuild in America. Especially considering Goodyear provided housing free of charge to any workers and their family. In fact, it was the only camp in the area to do so.

Cultural influence was strong – and some were threatened by it

Because of the ability to live on site, the workers were able to keep a close-knit connection to their community and culture. Children who grew up in the camps at the time often remark that they had the time of their lives – running around with their friends as their families worked the fields. There was a familial atmosphere to the place as well; there would be camp-wide celebrations for things such as Christmas, La Posada, Dia de Los Muertos, and more.

Though the celebrations and cultural traditions were held in high esteem within the camp, the Goodyears became frustrated with the cultural influence (insert eye-roll here.) When the workers decided to build a church on the premises in order to continue their religious practices, the Goodyears were fine with it. However, not until the church looked far too Mexican for their liking. They hired an architect to come in and change the church’s facade to reflect a more Roman Catholic styling versus a Latino Catholic styling.

The church also held a landmark significance for the community. Connected to the church was the cemetery, which the Goodyears had established after a flu epidemic swept the camp, killing hundreds.

Minimal remnants of the site remain

Now known as Litchfield Park, the current homes and businesses that reside on the land may not have been possible were it not for the Mexican workers who put their blood, sweat, tears, and in some instances lives, into the soil.

The only reminders of the labor camp that remains are the St. Thomas Aquinas church – and the cemetery. The rest was torn down in the 90s to make way for retail and residential development.