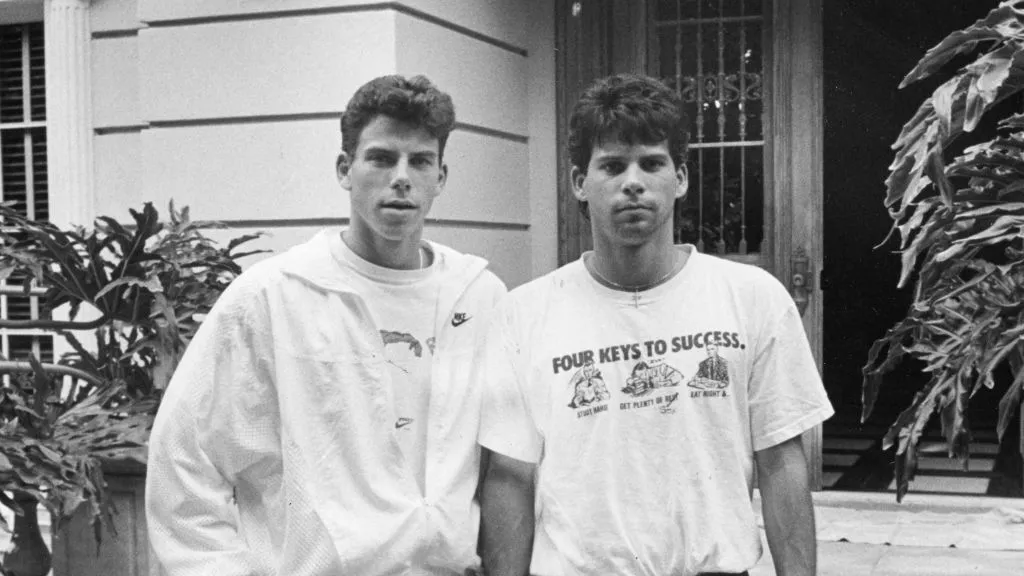

Image courtesy of Nuestro Stories.

He was a guerilla by 14, published by 20, imprisoned by 30, and exiled by 36. For all intents and purposes, Reinaldo Arenas lived more than one life in the short time he graced this planet. His flowing narratives and deeply introspective work bravely exposed the wounds inflicted by the Cuban government and earned critical acclaim. His story is also the story of thousands who were left voiceless under the Castro regime. Stories born of pain and repression. Stories that spoke to the beauty of freedom, found after decades of hatred inflicted upon him and so many others under the Cuban government.

Arenas’ Writing Journey

Born to a single mother who fostered his creativity and love of writing, Arenas was alive during the second presidency of Fulgencio Batista. The US-backed dictatorship led to the demolition of Cuba's middle-class and widened the gap between the rich and the poor. In order to control his public perception, Batista enacted strict media censorship laws. Anyone found going against those laws could be violently tortured and executed publicly. When the Castro-led guerillas arrived in Cuba, Arenas felt compelled to join up, at the age of 14. His enlistment didn’t last long, however, after what Arenas described as ‘witnessing the injustices perpetrated by the guerillas’ and went back to school, eventually graduating with a degree he had no interest in. After leaving school, Arenas continued the passion he had been taught by his mother. Writing.

By the age of 20, he was invited to work at the Cuban National Library and it was during this time that he began writing his first works. It was also around this time that Castro began to view the library as a source of ‘ideological corruption’ and started systematically banning books that could be viewed as suspect. In fact, Arenas’ first book “Singing From the Well'' only had 2,000 copies printed before it was banned for going against the Socialist Realism requirements introduced. His second book, “Ill Fated Peregrinations of Fray Servando'' was also banned – but Arenas was able to smuggle it out and have it published overseas. Both openly discussed homosexuality, which was highly dangerous at the time. By 1967, Arenas had been placed under surveillance.

His surveillance aligned with the introduction of UMAPs – forced labor camps created under Castro with the intention of imprisoning homosexuals and forcing them to renounce their sexuality. Police would round anyone up who presented as “effeminate” or who dressed in a “hippy, counterculture style” regardless of whether a crime occurred. Along with the forced labor, detainees were subject to varied forms of torture; reports indicate prisoners were beaten, tied up naked with barbed wire, and buried in dirt up to their necks to entice their renouncements. Arenas himself managed to avoid imprisonment until 1973.

Read more: Freedom Tower Is One of Miami’s Most Beloved and Famous Historic Sites

After being robbed on the beach, Arenas reported the incident to the police; but the encounter with officers exposed Arenas as a homosexual, and he was subsequently arrested. After he was taken in, it was discovered that he had published his work outside of Cuba despite the ban.

He was not in jail long before he escaped and went into hiding. Illegally obtaining a room to rent, he began to write his autobiography “Before Night Falls'' but was recaptured before he could complete it. Placed into solitary confinement, he was questioned constantly about the people who helped him smuggle his work out of the country. Rather than act as an informant, Arenas made his first attempt at suicide.

His Freedom was Short-lived

Arenas was eventually sentenced to eight years for ideological deviation and publishing banned work abroad. He was forced to renounce his own work through a written statement, as well as declare that he was ‘counterrevolutionary’ and ‘detested homosexuality’ as part of his punishment. A story that mimicked hundreds of thousands of others who found themselves rounded up and arrested for their sexuality, how they presented, or something as simple as their fashion, during the Castro regime. Though released early, it wasn't until 1979 when Arenas discovered true freedom, when Castro began granting ‘exit permits’ to people he no longer wanted in Cuba; political prisoners, old criminals, mentally ill, and homosexuals, among others.

Arenas lived the rest of his life, however short, in the United States. First in Florida, then eventually settling in New York City. In 1990, Arenas took his life after being diagnosed with AIDS three years prior. In a note left behind he wrote:

Due to my delicate state of health and to the terrible emotional depression it causes me not to be able to continue writing and struggling for the freedom of Cuba, I am ending my life…. I want to encourage the Cuban people out of the country as well as on the Island to continue fighting for freedom. I do not want to convey to you a message of defeat but of continued struggle and of hope. Cuba will be free. I already am.