Image courtesy of Nuestro Stories.

The history of Latinos in the U.S. is a complex one that encompasses more than 20 nationalities and territories and spans centuries, colonial conquests, slavery, forced migrations, and an ongoing struggle to be seen and heard.

Compressing this rich story into just 4,500 square feet of exhibit space is everybody’s definition of impossible. And yet, that’s what the Smithsonian has achieved with its first-ever Latino exhibition, “Presente! A Latino History of the United States,” which debuted Saturday.

Housed inside the new Molina Family Latino Gallery at the American History Museum in Washington, DC, the immersive, bilingual exhibit is a precursor to a future National Museum of the American Latino. It’s expected to take ten years or so to fundraise for and build the estimated $700 million Latino Smithsonian.

We had a chance to tour the gallery before its public unveiling, and, in general, it’s an impressive first effort with some understandable holes to complete. Here’s a look at what we think works — and doesn’t — at this ambitious exhibit that largely draws several hundred articles and items from the Smithsonian’s own collections.

Technology is creatively embraced — and its possibilities are exciting

While Latinos may be frustrated that the Smithsonian took so long to honor our history, this delay is certainly going to reap one huge benefit: our future museum will feature the most state-of-the-art tech. That’s the first impression you get when you walk into the gallery. Much the way mirrors make spaces look bigger, tech walls and kiosks not only visually decorate the gallery but also extend the exhibit’s storytelling with immersive videos, and photos.

The tech is not just visual either. At an emotional Cuban raft display, visitors are invited to press a button that simulates the scent of ocean water. A domino-playing exhibit features the aroma of fresh-brewed coffee, and a bread-making display triggers the scent of fresh bread. These clever multisensory details create many exciting possibilities for the future when curators will be able to design history that leverages other tech like augmented reality.

One of the largest digital displays you’ll find in the gallery’s multimedia plaza, El Foro (The Forum), is devoted to informing the public about the size, demographics, trends, and distribution of the U.S. Hispanic community. It’s a curious Hispanic 101 integration into the show that seems necessary given how overlooked and misunderstood our community still is today.

An Inclusive Exhibit Featuring ‘Many Latinos’

Given many sensitivities about recognition in our Latino communities, being inclusive and fair to the entire Hispanic cohort at a museum like this is one of those areas that if not skillfully handled could cause consternation and controversy among some.

Fortunately, in this regard, the Smithsonian has nothing to worry about. Despite — by their own admission — not being able to feature every single nationality, the inaugural program shows good faith in integrating as broad a spectrum of people and objects as possible from almost every sector of the Latino experience.

You could see that the Smithsonian was heading in this inclusive direction before the gallery opened. They made that statement the moment they chose the Cuban flag dress of Afro-Latina Salsa Queen, Celia Cruz to become the featured historic object of all their marketing materials. And while our beloved Celia serves as the gallery’s spiritual godmother (Selena would have been another great choice), the Smithsonian goes much further than that when representing Afro-Latinos. Afro-Latinos are prominently highlighted in displays about slavery, their early rebellions, and even through the civil rights efforts of baseball star Roberto Clemente, who makes a few cameos.

The Latino LGBTQ community is also well represented in the gallery. On exhibit, for example, is a stunning blue dress that belonged to legendary drag performer and activist José Sarria, who in 1961 became the first openly gay person to run for public office in U.S. history.

The gallery’s Somos Theater itself is sponsored by entrepreneur and activist Henry R. Munoz III, who chairs the Smithsonian’s National Museum for the American Latino board of directors, and who for decades has been one of the museum’s most powerful champions. One of the gallery’s digital displays also features an interview with Ruby Corado, founder of Casa Ruby, a bilingual LGBTQ community center in Washington.

The Exhibit is Deep on Struggles but Lite on Cultural Contributions

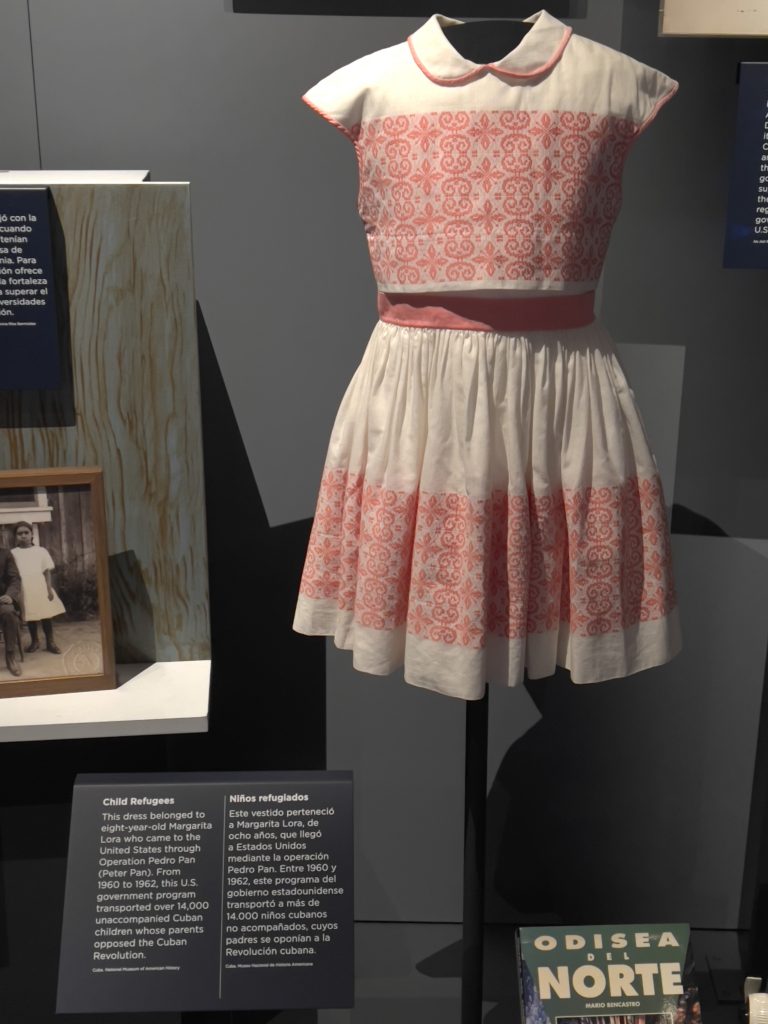

In Presente, the Smithsonian does a great job of expertly knitting together how our various Latino communities arrived where they are today. They achieve this through brisk storytelling that discusses many historic periods. The museum gives us a snapshot of pre-colonial indigenous America, the Spanish conquest of the Americas, slavery, the birth of Mexico, the Mexican-American War, Puerto Rico’s annexation, U.S. interventions in the Americas, the Cuban exodus from Fidel Castro’s Revolution, the Farmworker Rights Movement, and more.

Unfortunately, as interesting and necessary as this part of our Latino story is, it feels like the museum focuses too much of its limited space on our communities’ numerous struggles and not enough on our cultural contributions.

While our historic battles, national and international, are important, with this inaugural gallery, curators should have better balanced our struggles with our community’s fun cultural roots so it doesn’t feel as “heavy” as it often does.

For example, Puerto Rico’s contributions to music genres like Salsa, Latin Jazz, and Reggaeton were a simple, obvious opportunity to integrate a fun pop-up display. An even bigger miss was not creating a standalone display for Celia and Roberto Clemente, two cultural icons with universal appeal, who would have been much better for the gallery than the large exhibit space the museum devotes to an old printing press that wasn’t even directly involved in publishing the first Latino newspapers. (The printing press belongs in a much larger Latino Smithsonian).

NBC News reports that in two years, the next Smithsonian Latino exhibit will focus on “youth activism and empowerment.” That’s a noble idea but would be a huge mistake because it would follow the same “struggles” theme of the current exhibit. What the masses need to see next are joyful, cultural stories. That’s what moves people’s hearts and minds. (Just ask the American History Museum what their No. 1 draw is: Dorothy’s red ruby slippers from The Wizard of Oz).

Other Standout Pieces at The Molina Gallery

Even though history museums can sometimes overuse modern art pieces to fill in for original items they lack, there is one terrific exception to that at the Molina Gallery: the Tree of Life. Created by third-generation ceramic artist Verónica Castillo, this gorgeous artwork features small ceramic pieces representing the groundbreaking Latinos and Latinas that are part of the first exhibit, including the first Latina astronaut Ellen Ochoa, baseball star Mariano Rivera, and even Dr. C. David Molina, whose philanthropic Mexican American family donated more than $10 million toward creating the gallery.

You also don’t want to miss the “Dave’s Dream” 1969 Ford LTD Lowrider that the museum has parked in the lobby of the American History Museum to “drive” visitors to the Molina Gallery. This whimsically illustrated car is symbolic of the importance of lowrider culture among Mexican Americans and is named for the late David Jaramillo of Chimayo, New Mexico, who began customizing it in the 1970s and won several “first” or “best in show” awards with it in area competitions. (This vehicle also definitely belongs in the future museum).

The Latino vs. Latinx vs. Hispanic Debate is Settled — Sorta

One of the more curious parts of the exhibit is that the Smithsonian felt compelled to explain with a large sign why the gallery variously alternates between using the words Latino, Latinx, and Hispanic. The museum wisely settles this debate by informing visitors that they will allow people featured in the gallery to self-identify however they prefer, including by their gender and nationality.

Telling the Cuban, Salvadoran, and Nicaraguan Exodus Stories

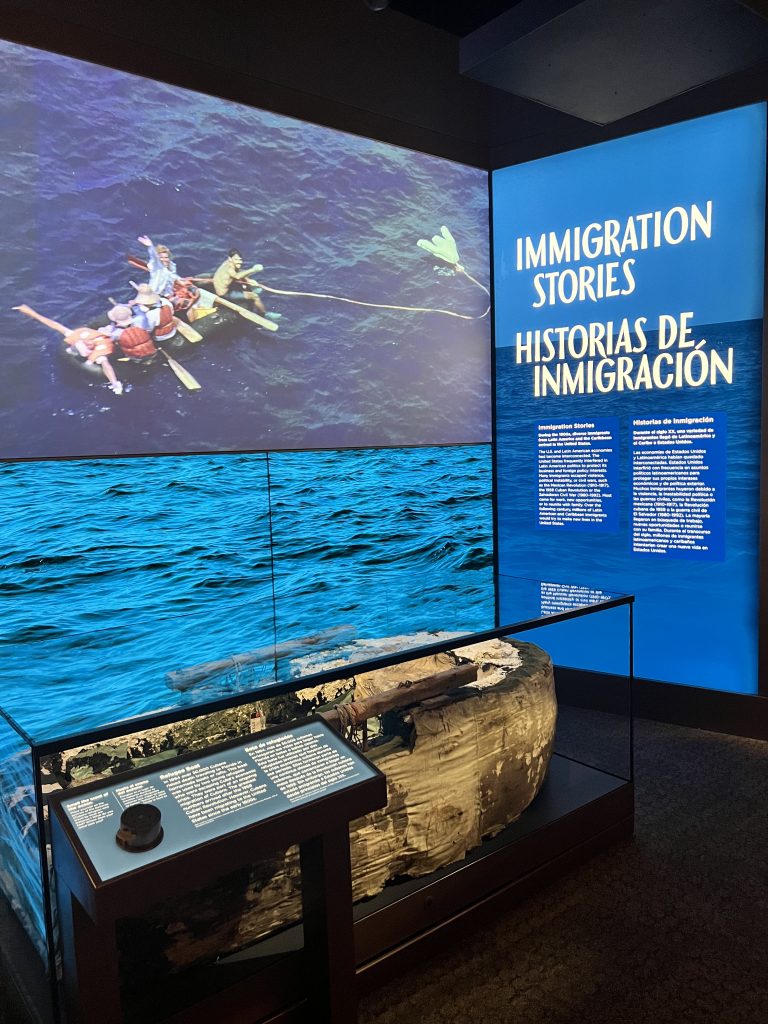

The Smithsonian doesn’t flinch in documenting our nation’s role in directly and/or indirectly triggering political conflicts that at times led to several historic mass exoduses to the U.S. from countries such as Nicaragua, and the Dominican Republic, Cuba, and El Salvador.

It also doesn’t give the Castro Brothers’ dictatorship in Cuba any cover, which will be a huge sigh of relief to many Cuban exiles who sometimes wonder if other Latinos notice that the Castro Dictatorship has been going strong for 63 years. Even though the museum doesn’t make any direct statements against the Castros, they actually tip their hats to Cuban exiles – maybe all exiles - by prominently exhibiting the tiny wooden raft that two Cuban refugees used to reach the U.S.

In this gallery, the raft transforms into an eloquent and universal symbol of the grit and determination that drive many Latino immigrants to reach our shores and borders in search of freedom and opportunities.

What’s Next

If every journey begins with a single step, the Molina Gallery is not merely a step. It’s a giant leap for Latinos, and a tribute to the Molina Family, Muñoz, leaders of the FRIENDS of the American Latino Museum, a cadre of bipartisan elected officials in the Senate and Congress, as well as countless others who spent almost three decades lobbying Congress to pass a bill enabling this museum to raise the funds to be built. Expectations are also high after the Smithsonian made the great move to appoint Jorge Zamanillo, a gifted leader who led HistoryMiami as the Founding Director of the National Museum of the American Latino.

The next phase for the museum is on a location to build it and the consensus is that it will be announced towards the end of this year or the very beginning of 2023. From private advocacy meetings we witnessed with many, including Republican and Democratic leaders, there is a very strong chance that the site will be on the National Mall. That’s the hardline position that the FRIENDS of the American Latino Museum, Muñoz, and others Latino leaders are taking, and it is absolutely right because Latino history is American history, and this museum deserves to stand “shoulder to shoulder” with the other great Smithsonians.

If you want to visit the museum virtually, you can see many parts of the gallery online at the exhibit’s website, https://latino.si.edu/. In addition to featuring more in-depth information about different parts of the museum, you can use the website to make a donation towards the construction fund for the building at this link.

W2lwYW5vIGlkPSIxIl0=

https://draft.nuestrostories.com//wp-content/uploads/2022/06/Manny-182x250.jpeg

By Manny Ruiz.

Manny Ruiz is the Publisher, Co-Founder, and Chief Historian of Nuestro Stories, which is the flagship media property of Brilla Media Ventures. The founder and former CEO of Hispanicize, and Hispanic PR Wire, Manny is a serial entrepreneur who began his career as a crime reporter for The Miami Herald. Manny holds a Bachelor of Arts degree in History from Florida International University.